Breadfruit

__________

Lungs

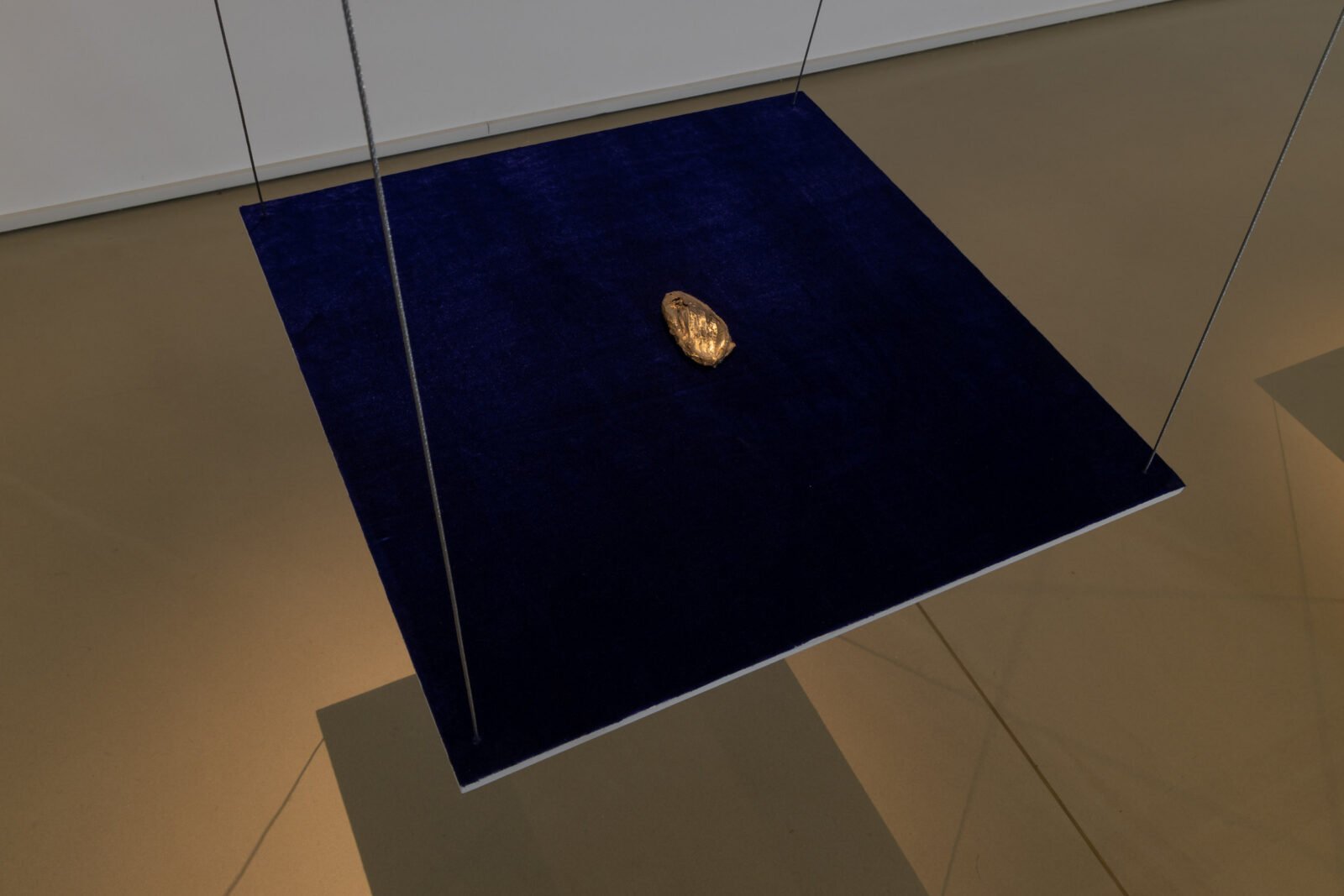

The shadows are what I noticed first. In one of Kedisha Coakley’s works, two dark masses resembling lungs mirror each other. Hovering above them on a clear platform suspended from the air are two bronze objects. Seconds after looking at them, I knew what they were: slices of breadfruit. I smiled in recognition. I could tell by the size of the wedges – too big to be a citrus – the absence of seeds, and their smooth texture. Memories of the first time I tried the fruit in Jamaica with my mother and extended family floated to the forefront of mind. Even my tastebuds seemed to remember.

I repeated this as I walked around the collection of hanging plinths displaying the other works in Coakley’s Horticultural Appropriation:Settlement (2022) series at Site Gallery. Walking through her areas of the gallery space, I identified mango seeds and tamarinds. The other fruits, which Coakley would later tell me are the tops of persimmons and cotton seed pods, I could not identify at first, but knew instinctively were some type of tropical vegetation. Bronzing these plants and placing them on plinths, elevates and preserves them both physically and figuratively. The same treatment is applied to the Afro-Caribbean history and culture they symbolise. The metal gives both heft. The regard Coakley shows for these fruits and seeds evokes comparisons with Veronica Ryan’s work, which also makes use of tropical flora. However, where Ryan’s work holds these objects delicately as they transition from utility to obsolescence, Coakley’s approach connotes a sturdy permanence. In casting not only the edible parts of the fruits, but their peels and shells as well, Coakley’s nods to the omissions in the recorded history of the centuries’ long relationship between the UK and the Caribbean. Her use of bronze signals a defiance against the possibility of worthlessness as if to say that even in their incompleteness they are precious.

In describing these works, Coakley begins with her upbringing in a Jamaican household. She tells me that her father, who was a Rastafarian, believed in “healing through the land”. From his practices and beliefs she has gathered traditions and oral histories around foods and medicines that have been passed down through generations and across continents. “When [these foods] have been extracted they leave knowledges and communications”, the artist tells me. This information has been reappropriated, rediscovered and subsequently rebranded as new or trendy in the UK and other former colonial powers. This process is not dissimilar to the one experienced by the lands these plants are native to centuries prior under colonisation. For Coakley, Horticultural Appropriations: Settlement is about retelling the stories of these objects from the perspective of the communities that know them intimately, having embraced them before they became mainstream wonder cures and popular salves.

This reclaiming extends to Coakley’s curation as well, which she acknowledges takes a colonial approach. “Some may say I’m mimicking the Wunderkammer *– yes, I am because I’m reclaiming those spaces, and I’m addressing what they are.” However, her choice to suspend the plinths reflects departure from this . The artist chose to hang her plinths from the ceiling positioning them slightly below sight lines to enable audiences to touch and handle the works. Although touching the objects wasn’t ultimately possible in the context of this exhibition, Coakley still wanted to facilitate a closeness with s her work, allowing people to be “near enough to smell the metal” used to create these objects. Tactility, and the sort of intimacy it brings, departs from a colonial mode, which focuses on accessing history primarily through the visual. Coakley acknowledges the necessity of avoiding touch to preserve more delicate artefacts, but highlights the information missed by engaging with history through only one sense, usually the visual.

Coakley tells me that she was inspired by Yinka Shonibare’s wind sculpture, which she saw at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Seeing this work of art outside of a white cube setting, standing bare in the landscape, encouraged her to aspire to a similar “undisturbed engagement” in her own practice. Her pared down approach at Site Gallery achieves this, but in this case, the gallery setting provides a breath to a voice long stifled.

* the Wunderkammer (German, ‘wonder chamber’) – The term was originally used in mid-century to describe a room containing a private collection of rare natural history specimens such as corals, but above all curiosities such as mandrakes, misshapen antlers, or narwhal tusks. Wunderkammern were predecessors of natural history museums. Also sometimes translated to cabinet of curiosities.

Words by Salena Barry

Images: Documentation images from Horticultural Appropriation:Settlement (2022), part of Dark Echoes. Photos by: Jules Lister Photography, 2023.

About Platform:

Platform is an established artistic development programme at Site Gallery which allows artists to explore new ideas in a public space, testing new thinking and research with engaged audiences. It is funded and supported by the Freelands Artist Programme, a five-year programme that supports emerging artists across the UK in partnership with g39, Cardiff, PS2, Belfast and Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh. For this edition, the exhibition was presented across Site Gallery, Yorkshire Artspace and Bloc Projects.