Technological obscurities, personal complexities: Jan Hopkins’ meditation on how the self and mechanical intertwine.

How technology and emotions interweave and inform our lives is not always readily apparent, yet within a technologically driven world, its affective response is inevitable. People share the most joyous and horrifying news via Twitter; the intimate lives of others are archived on Instagram; smartphones act as the mediator between close family and friends. Living and collaborating with devices means they are integrated into every aspect of our lives, psychologically and materially.

In Help! Jan Hopkins, an interdisciplinary artist, charters the dynamics of ‘control’ by illuminating the orchestration of different realms of the technological. She crafts her own words like ‘genoir’ (memoir) and ‘emotes’ (emotion) to bridge the disjunct between self and technological, through writing, craft, sculpture, drawing, and digital media – posing eternal, and indeed urgent, questions of language’s ability to reimagine automation and machinery.

In the middle of Site Gallery a large bench is coupled with a white open umbrella on a raised area, with white circular craft cutouts of ‘emotes’, placed upon it accompanied by a QR code in the left corner. Almost virus-esque in appearance; white circles with small lines dotted around them, the ‘Emotes’ which Hopkins articulates are ‘in the atmosphere and are hand-generated rings which resemble sobbing particles from mama garden, which is about working with technology and drawing from code’. Constructed through craft cutters, these curious formations tread the line of abstract while being entirely relatable, and indeed plausible. Scanning the QR code, the sculpture is brought into context: a video of Help! by the Beatles loads, and Hopkins’ bench is matched as the one from the video – time and technology are transgressed through this simple re-enactment. Humour and the charged reiteration of perhaps a cry for help, the vulnerability of the self through covid momentarily prevails: technology does evoke emotion in indirect ways.

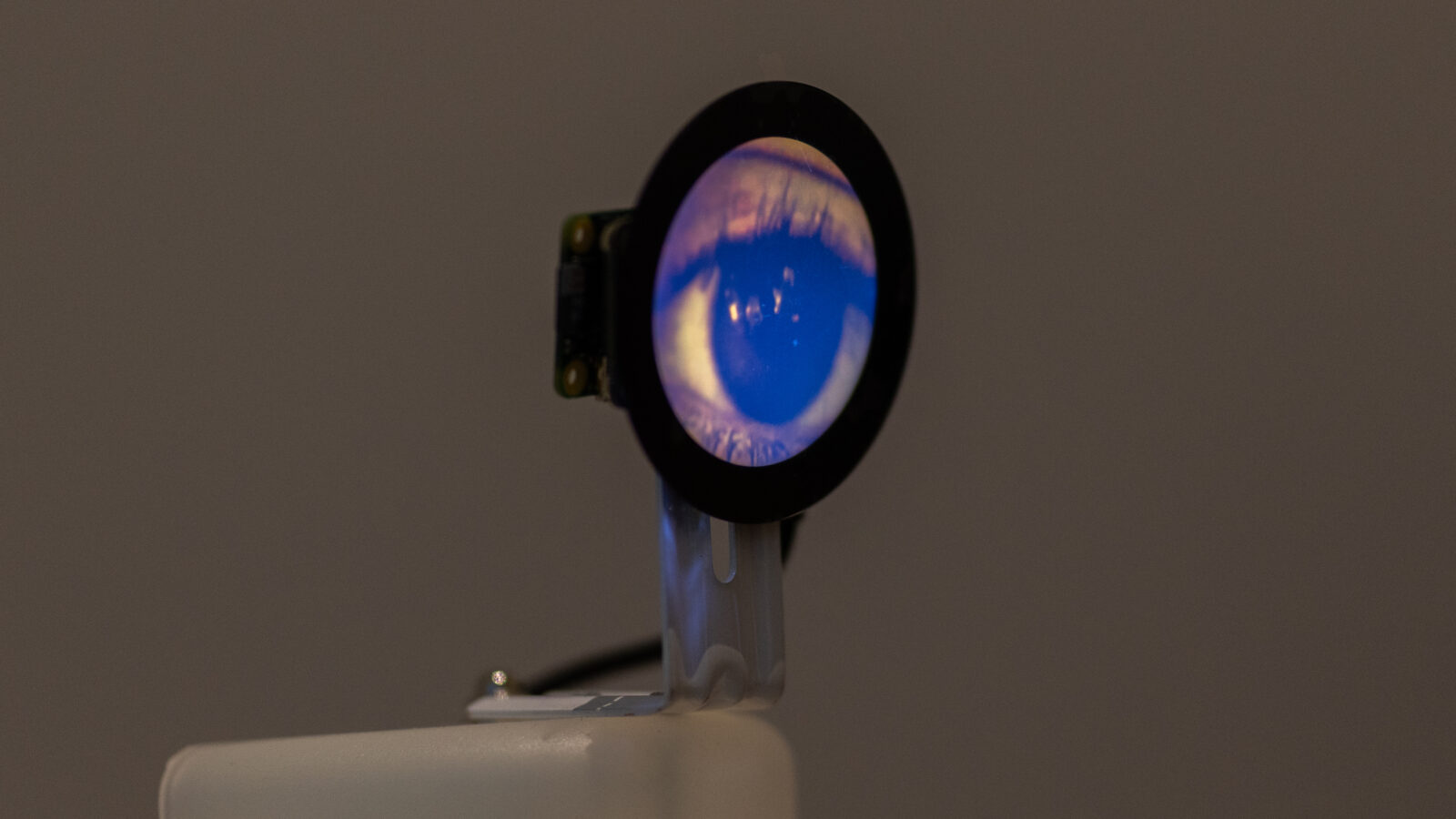

The next sculpture, The Fool on the Hill, is bizarre – the figure has an uncanny disposition with a video of an eye as a head, which both unsettles and provokes. Varied in form, colour and texture, orienting yourself in relation to the sculptural figure is required to grasp the complexity of it all at once. A white shirt is overlaid with a knitted vest, medical like wires protrude from the arms, a clock sits like a tie, an illuminated flower hangs from one sleeve, a record with a flower-power drawing sits within it, all of which sit upon a speaker. The eye is from Magical Mystery Tour, again by the Beatles, the knitted shirt was knitted by the artist and is a direct copy of the vest worn by Paul McCartney in the movie – even mimicking the grayscale colour palette of a black and white still from the film. Embracing these cliches, Hopkins demonstrates how an artwork can be creatively collaborative between artist and machine. The remerging of the Beatles functions as a nostalgic device that can be resurrected through the immediacy of the technological, weaving together Hopkins’ past and present as a ‘genoir’ (memoir).

The final installation, In My Life a ‘genoir’, is the most emotionally and conceptually ambitious piece where the title again references a Beatles song. Inside a glass cabinet, several items accumulate in a sentimental scene: 12-volt televisions from the 2000’s are placed alongside blue champagne glasses from her mother’s house, a radio plays and a wooden sculpture of a giraffe is accompanied by an orange lamp, all of which creates a cosmic domestic connection to Hopkins’ past. Emotes, projected above, shift and change with their centers ranging from letters to punctuation, all programmed by Hopkins’ son; when they touch, one pops, and new ones are generated. Flower power drawings infuse the sculpture with a sense of joy and freedom, as small pockets of aesthetic relief. Despite drawing and thinking being the biggest part of Hopkins’ practice, as a viewer, the greatest strength is found in this interdisciplinary approach to the past and future, where a non-linear, albeit intuitive sense of the self and others prevails.

Encountering Hopkins’ work there is the tacit feeling that she balances both personal visages of the past through the prism of the technological while asking the viewer to meditate upon their own lifelong relationship to the integration of technology in everyday life. References to the Beatles re-emerge, emotes create a unique artistic language, technology is given control and agency, interdisciplinary form and function are an encapsulation of the past in the present. These anomalies for Hopkins are embraced through the tentative reflection on the ‘genoir’ of her past in the present, as an archive of the myriad, multifaceted ways in which the peculiarities and unseen forces of the ‘technological’ can be reconsidered.

Words: Hatty Nestor

Hatty writes on gender, art, class and the law for a range of publications and newspapers. Find out more about her work here.

Photo credits: Shared Programme, 2022.

About Platform

Platform is an established artistic development programme at Site Gallery which allows artists to explore new ideas in a public space, testing new thinking and research with engaged audiences. It is funded and supported by the Freelands Artist Programme, a five-year programme that supports emerging artists across the UK in partnership with g39, Cardiff, PS2, Belfast and Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh.

For this edition, the exhibition was presented across Site Gallery, Yorkshire Artspace and Bloc Projects.